Munich memories: Bronwen Anders' path from JYM to pediatric advocacy

Bronwen (Jenney) Anders was a member of the 1961-62 JYM cohort. She majored in Russian at Mount Holyoke College before going on to earn a medical degree from Tulane University in 1968. Her experiences in Munich are a reminder of how all of us are connected to the historical events of our time, in Bronwen’s case: to Germany’s emergence from WWII, to the Cold War and to the beginnings of the protest movements of 1968.

Like so many JYMers, Bronwen maintained her connection to Germany and continued to hone her broader intercultural competencies long after her year abroad.

After moving to San Diego in 1982, Bronwen became a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There, she worked with the students and residents under her supervision in multicultural, underserved settings, such as community clinics, clinics serving Native Americans and a clinic in Tijuana, Mexico.

Her dedication to ensuring that all children have adequate medical care earned her several recognitions. In 2007, Bronwen received the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Senior Section Child Advocacy Award, which recognizes a senior member who has facilitated efforts to advocate for children in his/ her community. In 2011, she received the Leonard Tow Humanism in Medicine Award from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation.

In 2016, she received the Hillman-Olness Award for Lifetime Service and Lasting Contributions to Global Child Health. Bronwen herself generously established the “Bronwen Anders Pediatrician of the Year Award” for the San Diego Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP-CA3).

In 2003, Bronwen’s home was one of the 2,232 destroyed in the devastating Cedar Fire in San Diego County, California. She and her husband lost all their possessions, including many of Bronwen’s pictures and other mementos from her time in Munich. She still has many vivid memories of that year in 1961-62, however, on May 31 of this year, she met with JYM Program Director Lisabeth Hock on Zoom to share some of them.

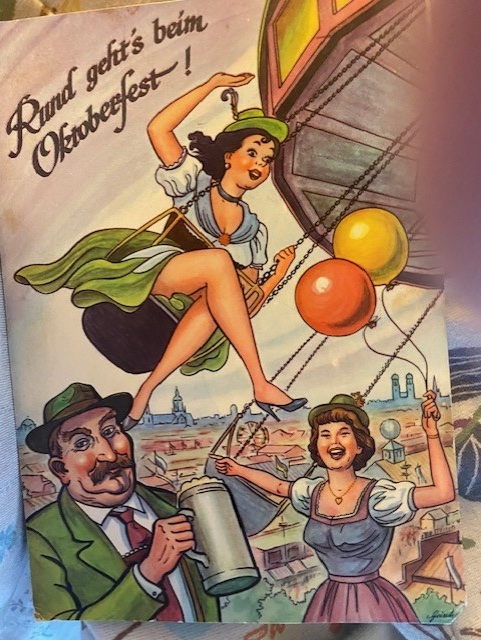

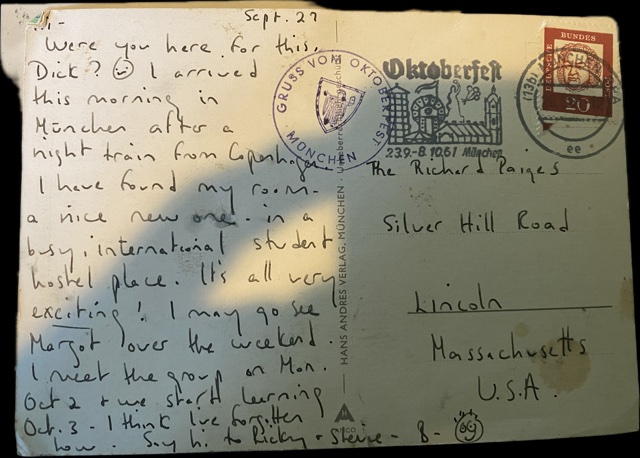

Bronwen’s journey to Munich began on the “Empress of Canada” ocean liner, which departed from Montreal. After arriving in Munich on September 27, 1961, she promptly sent her sister a postcard: “I arrived in Munich this morning after a night train from Copenhagen. I’ve found my room. A nice, new one in a busy international student hostel place. It’s all very exciting. I may go and see Margot over the weekend. I meet the group on Mon Oct. 2 & we start learning on Oct. 3. I think I’ve forgotten how.” Even today, the long break between the end of the second semester in the U.S. and the start of the first semester in Munich tends to cause study habits to rust a bit.

Of her hostel, Bronwen recalls living in a “little, tiny room” with “a couple of pictures on the wall” and a shared cooking space. Unlike today’s Munich, where it sometimes seems less and less clear when to address someone with “Sie” and when to use “du,” Bronwen’s hostel “was very formal. We called each other ‘Fräulein Anders,’ ‘Fräulein this,’ ‘Fräulein that.’”

Bronwen arrived in Munich six weeks after the Wall was erected around East Berlin on August 13. In this new phase of the Cold War, her most memorable class at the LMU was related to her Russian major: “I had written myself down as a Russian major because that was big during the time at Mt. Holyoke and they had an interesting group, a balalaika group and the old literature, and I was completely sucked into it.

In Munich, I remember vividly a small teaching facility in which I took what I’m thinking is some Russian—it wasn’t Russian language, it was more Soviet “Politik.” It was the only thing I could take related to my major. And I remember being the only left-handed person . . . in that classroom. It was all in German with a little bit of Russian. We’d pass around the Russian newspaper that I was supposed to translate into German. That was pretty stressful. I did that to keep up my major while I was there. It was the “Pravda” newspaper and I would hunker in the back so as not to be chosen to do the translation from Russian into German.” Most likely all JYMers, past and present, remember the stress of having to perform “auf Deutsch,” especially during their first weeks on the ground.

New friendships are central to the Junior Year in Munich experience and Bronwen remembers three particularly good friends. The first was the “Margot” whom she thought about visiting her first weekend in Munich. Margot was the same age as Bronwen’s mother. The two had met when Bronwen’s parents were in Rome in the late 1930s.

Margot took care of Bronwen’s then-one-year-old sister while her father was working on his dissertation. In 1961, Margot became a mother figure to Bronwen: “Margot grew up in Rottach-Egern and I loved the mountains and the trails. So, during the whole year I was there when I was lost, I would take the train down to change trains north of the Tegernsee, meet Margot and hike up to the top of the Hirschberg where they had a mountain hut. She was my kind of person. . . .”

Margot didn’t speak English and she and her husband taught Bronwen some of their dialect. An active member of the Tegernsee branch of the German Alpenverein, Margot also introduced Bronwen, whose love of mountains and trails started in southern Germany, to the local flora: “I had a photograph album of the time I spent with her in the mountains, with the pressed flowers and the labels in German, all of my favorite flowers from high in the mountains, including Edelweiß, the gentians.” Bronwen says she could find her way from Munich to Rottach-Ergren blindfolded: “My sanctuary became the mountains and the flowers.”

While Margot looked out for the college-aged Bronwen during her junior year, Bronwen tried to look after Margot in her old age, learning new parts of her older friend’s story. “Both of my grandkids visited her by themselves and got to know where she was in her older years. We visited her several times. My two sisters and I and my mother stayed in contact with her. She like many people I think had the guilt of not talking about war years. But later, finally at the end, opened up about them. . . . She was like a member of the family.”

Bronwen, of course, made friends among the JYMers. She was particularly close to Bryn Mawr student, Diana Oughton. Diana did volunteer work in Guatemala the year after her graduation from Bryn Mawr and she became a member of the Michigan Chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society while studying at the University of Michigan.

She eventually joined the far-left Marxist organization, the Weatherman and died in the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion. Prior to those events, during the young women’s year abroad in 1961-62, Oughton was “a junior at Bryn Mawr from the Midwest, a simple person” and someone with whom Bronwen explored her new home: “We had bicycles that we rode around Munich together.”

Together with Diana, Bronwen met another of her good Munich friends: "We went to a Goethe Bar that seemed to be open and I don’t know exactly where or what, but it was in there that we met Walfried Müller, who was a young, blonde. attractive guy and we sat down and chatted with him because he’d never met Americans and we’d never met a pretty active communist. We shared hours and hours of conversation about our lives and his life and I remained in contact with him for many, many years. He was apparently fascinated by these two American girls who came from not rich families and were riding bikes in Munich."

Even when one has friends, the holidays can be lonely for students in Munich and gifts from home seem particularly precious at such times: “My parents sent me a Christmas stocking that was wrapped up and I had to go to the post office to collect it because the package had broken open and I had it in the basket in my bike with the stuff falling out of it . . . I had my Christmas stocking that I had taken back and opened up in my little room by myself.”

Notably, Bronwen found an antidote to holiday loneliness in helping others, a form of engagement that would continue through her long career as a medical doctor: “Then I spent the night or two with this Protestant nun in a town a little bit north of Munich, going from house to house to poor people’s homes . . . Now I have sisters down in the Tiuana slums . . . we’ve worked together to help build health systems for the Kumeyaay [indigenous peoples] that live south of the border . . .It’s the same thing all over again. These sisters dedicate themselves to the poor. And I spent that Christmas morning going with that Protestant nun into all of the poor places.”

Her love of languages and her desire to do volunteer work stayed with Bronwen. Her children were born overseas. She and her husband have done medical work internationally. Working cross-border to help build back indigenous villages’ health care systems after COVID, she sees herself as “continuing the community health work begun in Munich.” Echoing many JYMers, she says, “I think Munich and my experience there has probably been more powerful in my life than anything else . . . It’s the German and the mountains that I love.”