The incredible value of my junior year in Munich

Fred Stahl, a JYM alumnus from 1958-59, shares his experience with the Junior Year in Munich program and how it impacted his career and life.

Contributed by Fred Stahl, JYM Class of 1958-59

I began my college study in 1955 at Wayne State University in Detroit. It was a good choice. I qualified for advanced classes in literature, writing, sciences, computers, math, and German. After a couple of years of study in liberal arts, I was delighted to discover that Wayne State offered an unbelievably wide selection of fascinating courses as part of America’s oldest study abroad program: Junior Year in Munich. All courses were taught in German! I signed up.

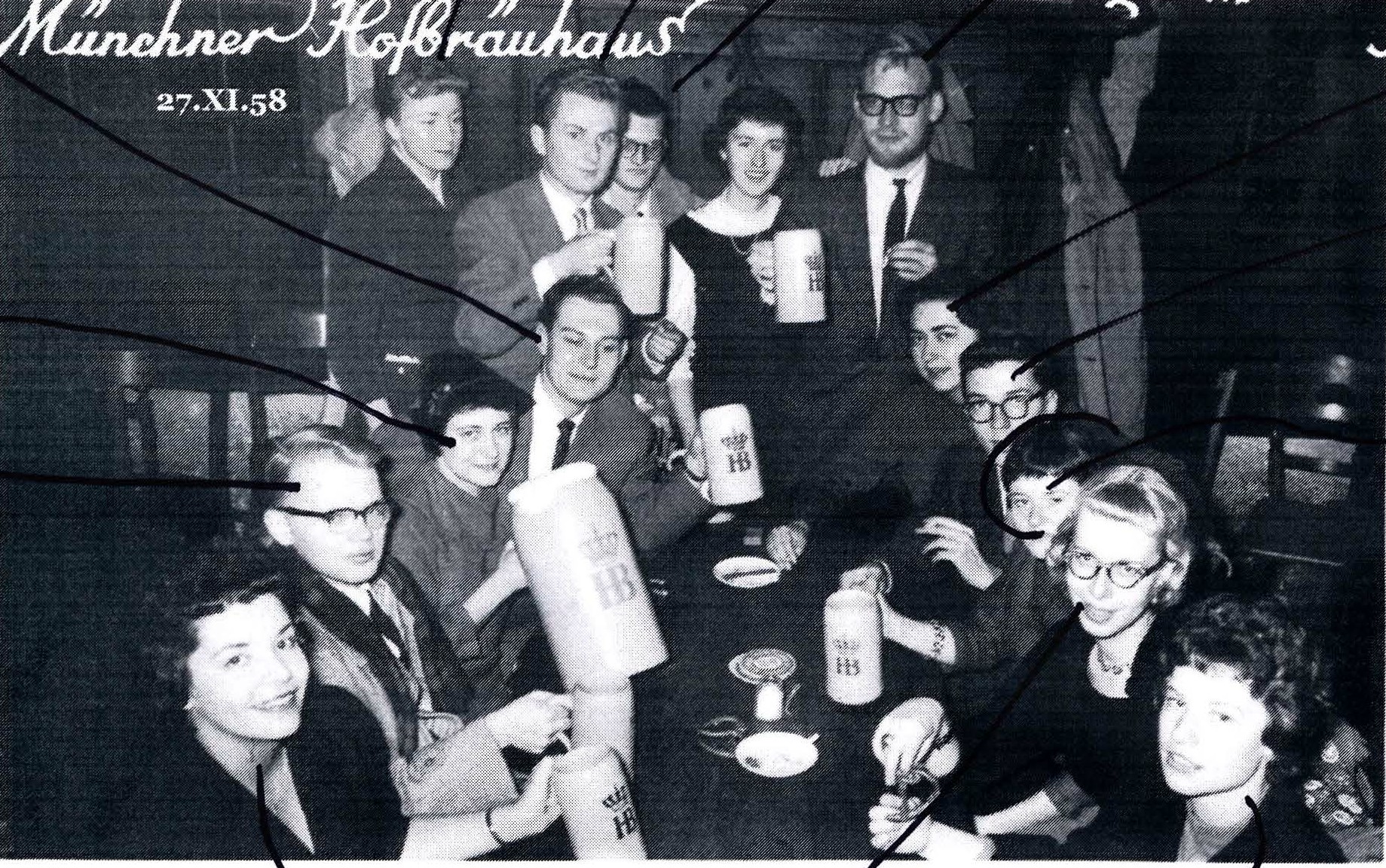

Fred Stahl is the fourth head from the left in the back row.

In September of 1958, I and around 40 other JYM students from various American colleges left New York on an ocean liner headed for Europe. It was old and slow, so we had seven days at sea to meet our new classmates before we arrived at Le Havre, France.

I found my fellow students to be friendly, smart, and adventurous. We shared a compelling interest in German culture, society, entertainment, food, and, of course, beer.

When we arrived at Le Havre, our group was pleasantly surprised to learn that JYM had organized a couple of sightseeing stops during our journey to Munich. The first was Paris, where we stayed three days in student housing while touring the city, followed by a one-day visit to the American Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Brussels. Then on to Munich.

Once we were settled into our quarters in Munich, the staff at JYM helped each of us design a one-year program of study by combining courses taught by JYM instructors with a selection of courses offered at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. I signed up for JYM classes such as German history, literature, and language. At the university, I had physics, math, and sciences.

Despite only two years of German back home, I got passing grades in all my classes in Munich, thanks to the two most fascinating and friendly instructors I ever had: Frau Doktor Marianne Riegler and Herr Albert Reh. Frau Riegler was unforgettable. Her brilliant mind, worldly knowledge, talented teaching, firm classroom discipline, complete devotion to her job, and big-hearted personal friendships with students, made her one of the most amazing people I have ever known. After she finished the 1958-59 school year in Munich, she went to Detroit for a year as a visiting faculty member in the German department at Wayne State University.

December 1958 at the JYM Christmas dinner.

She returned to JYM in 1961 as resident director, a position she held for many years. Her memory touches my heart ever since I left München over sixty years ago. Herr Reh was also an excellent instructor. He shared his experiences as a soldier in the German Army during WW II, including being captured and put into a Russian prisoner-of-war camp.

While at sea, we students discussed what we looked forward to doing in Munich. Our thoughts included exploring restaurants and beer halls, visiting local museums and historic sites, and going to plays and concerts. Of course, almost everyone wanted to go to the Hofbräuhaus in the Oktoberfest, the world’s largest Volkfest. Unfortunately, Oktoberfest closed a couple of days after we arrived, so most students missed it. I did not. I took a bus to it the evening of the day we arrived. It was an incredible event to experience.

My classmates and I discovered the historic Münchner Hofbräuhaus restaurant in the center of the city. It became a favorite place for us JYM students and friends to enjoy the best Bavarian food, drinks, and atmosphere.

Fred Stahl's photo was taken in 1959.

Many of us traveled to see other cities in Europe while at JYM. Some trips were funded and arranged by JYM. Various groups of students took self-funded tours. I recall visiting maybe a dozen interesting cities in France, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, and, of course, Germany. I hitchhiked from Munich to Berlin and Madrid during the January holiday break.

While in Berlin, I photographed the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church on Kurfürstendamm in Berlin. The damage it suffered from a bombing raid in 1943 is still visible today. It was in 1959 that I received a great honor. I was the first American since the war to be invited to join a German student fraternity in Munich. In 1958, a student member and I met in a history class and became friends. He invited me to meetings and events in his fraternity. I found a new world of friendly and interesting Corpsbrüdern. In January of 1959, they offered, and I accepted a lifetime membership. I have visited my Corpsbrüdern in the Corpshaus many times over the sixty years since my return to the U.S. in 1959, often to participate in special events.

My year at JYM completed my four-year undergraduate program at Wayne State in Detroit. When I returned to the U.S. in September of 1959, I collected my undergraduate diploma and began graduate studies in liberal arts and computer science.

After my second year of graduate school, I began a full-time career while continuing to take courses needed for my degree, which I received in 1963. Much of my career in the sixties and seventies focused on supporting U.S. government agencies and aerospace companies by using computer models to evaluate designs of aerospace products. In 1981 I was working at McDonnell Douglas (which later became part of Boeing) when I was asked to create and lead a team called the Lean Manufacturing Assessment Project. Thanks, to my international experience beginning with JYM, my team of engineers and I could conduct on-site studies of the organization and management of the world’s most efficient factories in Europe and Asia.

As the world aerospace market expanded, it became clear that Boeing needed someone to track the international aerospace business and national and international government aerospace agencies and ministries of defense. My trips and contacts in Germany, Europe and Asia over the years since JYM made me a prime candidate for the job. In September of 1989, Boeing appointed me as its chief scientist for Europe. On September 19 of 1989, my wife and I arrived at our new residence in an apartment in Bonn, then the capital of Germany. On the night of November 9th, three weeks after we arrived, crowds of long-suffering East Germans forced their way through the gates of the Berlin Wall. The Fall of the Wall triggered historic political and military turmoil in East and West Germany, as well as in Eastern Europe and Russia. Over the next two months, the situation grew increasingly unstable. The threat of extreme political, social and economic upheaval and collapse—and even the possibility of military action—hung in the air.

In contrast to my direct exposure to the turmoil in Europe, the US press coverage seemed relatively shallow. Print media took little note of the looming chaos. By January 1990, I decided that Boeing’s top executives needed better reporting to comprehend Europe's alarming political, social, and economic upheavals. So, I began sending compact dispatches about critical events to the company’s CEO, president, senior managers and overseas teams.

My goal was to help them comprehend, both consciously and intestinally, the important—and sometimes scary—social, military, economic, and geopolitical changes emerging in Eastern Europe, West Germany, and East Germany. The two Germanys were still separate states with significant political and military resistance to unification. About two weeks after the Fall of the Wall in September, I began sending expanded two-page biweekly dispatches called “NOTES FROM BONN” so I could report the wide impact of economic, political, and military events in Germany and Eastern Europe. At mid-year of 1991, the political and economic unification of East and West Germany with a common currency and the elimination of border controls changed everything.

On Oct. 3, I was delighted to begin sending news about the government, military, financial, economic, social, and political changes in the newly united Germany. I also reported that no one was helping Russia figure out how to bring home its 100,000 soldiers stranded in what was once East Germany. NOTES FROM BONN was popular. Its readership increased every month. I estimated its later issues were reaching more than a thousand readers. On Nov. 15, 1991, not long after the unification of Germany, I sent out the 20th and final issue. Three years after unification, my research in Germany found that around 1950 a huge aircraft factory was built at the Dresden airport. Who built it and what for what market? And then, in 1961, why did the East German government order the factory to be closed and all aircraft, delivered or under construction, to be destroyed?

the right and left wings are a single structure, connected through the fuselage.

I found the answers after I moved to Germany by searching out and interviewing manufacturing managers and engineers who had worked in the factory in the 1950s. Their story of the factory began in 1946, a year after Germany surrendered. The Russians occupied the eastern zone of Germany and then had four major high-tech German aircraft companies that employed some of the most talented aviation minds of the time. At 3 a.m. on Oct. 22, 1949, Soviet soldiers with machine guns appeared simultaneously at the homes of the aircraft specialists in Germany while trucks with more troops waited in the streets. “We were abducted by the Russians,” one long-retired engineer told me. “We had four hours to gather up our belongings.”

The Russian soldiers locked the 530 engineers, scientists, mechanics, and metal workers they kidnapped in a train that then left for Eastern Europe. Two weeks later they arrive in Podberez’ye, a small Russian town 75 miles north of Moscow. The Soviets had filled its abandoned buildings with machinery scavenged from German aircraft manufacturers. The Russians then forced the transplanted engineers to continue producing the military aircraft they had been designing and building in Germany when the war ended. So, beginning in 1949, the aircraft the Germans produced was going to the Russians. After four horrid years, working for the Russians ended. After Stalin died in 1953, the new leadership in Moscow decided to release the captive German aerospace technicians who had been designing, building, and testing aircraft for Russia. In 1954, Moscow sent them with their blueprints back to Dresden in Germany, along with some funding to help them realize their dream of producing civilian airliners.

East Germany built a huge factory for the returning engineers on what had been a military airbase near Dresden and hired thousands of workers for the factory. Amazingly, in less than five years, they delivered the factory’s first four-engine jet airliner, the Model 152. It had its first flight in 1959.

While the Model 152 was in final assembly to save time and money, the engineers put into production a bomber they had designed for the Russians but never built. Like all bombers, it had high wings. They could not afford to redesign the airplane with low wings. So, there was no room for carry-on baggage compartments over passenger seating. Instead, there was a baggage room at the back of the passenger cabin. While the Model 152 story looks like a success. The reality is that it did not have a happy ending. On March 4, 1959, the engines of the first Model 152 failed as it was approaching its home airport, Leipzig. It crashed and exploded.

Retired engineers who had worked at the factory in the 1950s told me that by the time of the crash, the East German aircraft industry had become a huge business failure. It had been losing money for years. It had few customers. Its projects were far behind schedule. The Model 152s were far from competitive with new European and American airliners. The crash was the last straw. The orders from East Berlin were clear: the crash was to be kept secret and the wreckage was to be buried. In April of 1961, Berlin announced that aircraft production would be terminated immediately. All aircraft, already on the field or still in production, were to be destroyed. Tens of thousands of workers were dispersed to other industries. The factory doors were locked. Inside, men with axes broke up the airframes of the 26 Model 152s under construction. Hard aluminum alloys shattered under their blades. They cut up steel parts with torches. All business files and documents were sent to Moscow. The products of the dream disappeared without a trace.

In 1994, as I was finishing my research for the story of the Model 152, I told the staff at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington that I had uncovered the secret of what happened to East Germany’s aerospace industry. They said it was significant history and offered to buy the story. I delivered a 3,000-word article with 16 photographs, which they published in the March 1996 issue of the Smithsonian AIR&SPACE magazine with the title “The Rise and Fall of the East German Aircraft industry.” I am proud of what I have accomplished in my career. But I could never have done it without my time in Germany during my junior year in Munich.

Fred Stahl

October 5, 2022